By Suzanna Feldkamp

“Competitions have always been wild and crazy things. This year’s Casadesus seemed to exist in outer space.”

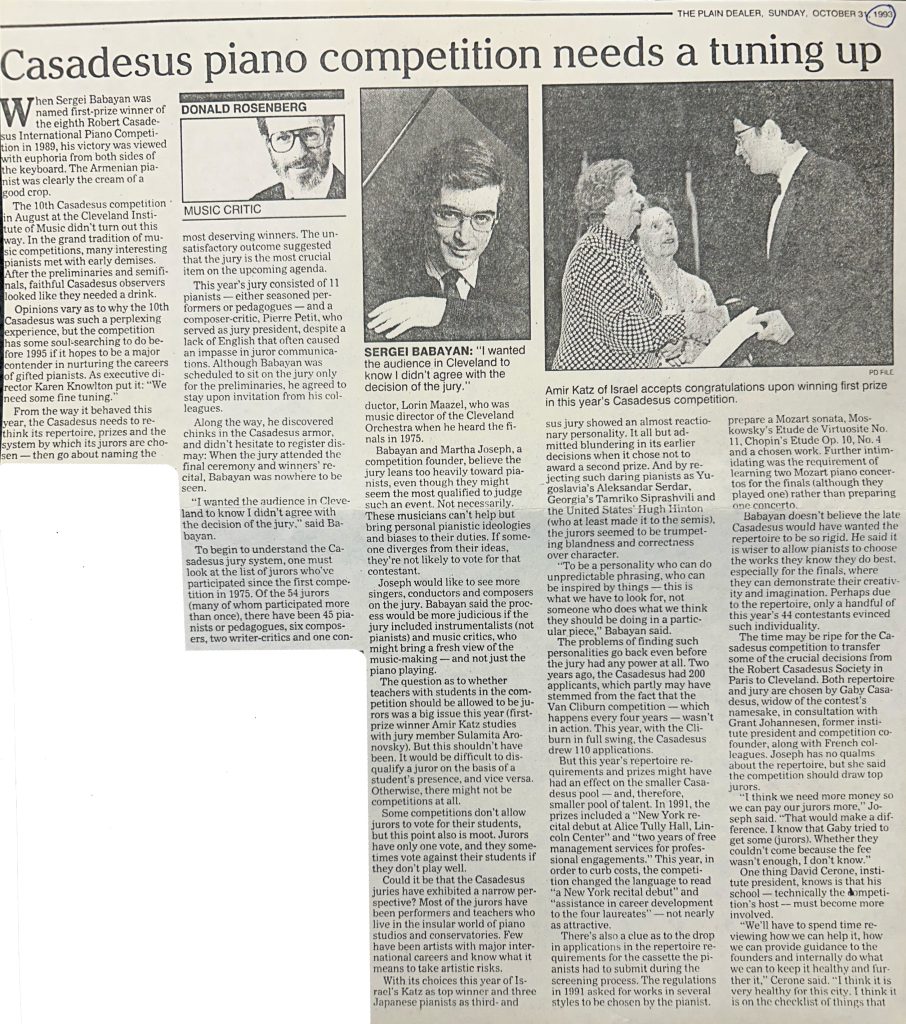

At least it did according to Donald Rosenberg, music critic for The Cleveland Plain Dealer in the 1990s and 2000s. After the CIPC of 1993, Rosenberg gave voice to the greatest pushback the competition had (or has) ever received against the jury’s choices. In a series of articles, he expressed continual surprise and frustration that the pianists he expected to advance to the next rounds were eliminated. By the end, he seems to have had two main complaints: 1) there was no second place and he didn’t like the reason why (that according to the jury, “there was too much of an artistic difference between Katz and his finalist colleagues to warrant a second prize”) and 2) he personally believed that more expressive pianists were eliminated earlier in the competition.

So Rosenberg had different opinions than the jury did. Why is that blog-worthy? Critics don’t always agree. The fiasco could have stopped with a single critic’s disagreement, but it didn’t—it blew up. Many of the avid fans of the competition relied on public figures like Rosenberg to help them assess the contestants. With his anger and frustration on display in the paper every day, some of these fans latched onto his critical opinions and took their complaints even further than his.

In fact, most of the relevant letters to the editor in The Plain Dealer are evidence of Rosenberg’s influence. Many of the folks who wrote in regarding their frustration about the competition results cited Rosenberg as either the source of their opinions or a major influence upon them. Some of these fans went farther than disagreeing with the results; some went so far as to suggest that the jury had been corrupt, that they had promoted their own students by eliminating anyone who might best them, that the jury was biased by nationalism… the list goes on, all the way to “we in the United States [are] losing our soul.”

A bit extreme? Probably. Even Donald Rosenberg had to backtrack in later articles. For one, he had never taken issue with Amir Katz’s performance or disagreed with the choice of Katz as winner: “Katz could turn out to be the kind of musician the competition seeks to promote—one who carries forward Robert Casadesus’ legacy of refined, magisterial artistry. At 20, Katz claims technical assurance and an interpretive sensitivity that should blossom in the coming years.” For two, “The question as to whether teachers with students in the competition should be allowed to be jurors was a big issue this year… But this shouldn’t have been. It would be difficult to disqualify a juror on the basis of a student’s presence, and vice versa.”

Rosenberg doesn’t seem to have had a problem with who won, then, or to have thought there was corruption in the jury—he was merely disappointed that the jury had different priorities. Rosenberg was a fan of individualized, expressive, and daring interpretations, but the jurors that year leaned into slightly more old-school stylistic preferences. They were looking for clean, elegant, reserved piano playing with utmost alliance to a composer’s markings. It comes down to a matter of taste, not a matter of correctness. Rosenberg even acknowledges the role of personal taste, writing, “These musicians can’t help but bring personal pianistic ideologies… to their duties. If someone diverges from their ideas, they’re not likely to vote for that contestant.” Did he remember that personal ideologies are also what led to his scathing reviews?

As Gaby Casadesus and Martha Joseph wrote in their letter to The Plain Dealer, “It’s fairly common that the audience and press vociferously disagree with the jury’s verdict.” Their letter was in defense of the jury—which Gaby Casadesus had been on herself—and she shot down any question that favoritism had been involved in their decision. They pointed out that the jury members were from eight different countries and the contestants themselves from dozens, arguing against the notion that national interests had been at stake. They also pushed back against the idea that teachers were prejudiced towards their students: “The fact is that the world’s top piano judges inevitably are also teachers who have understandably been called upon to teach the world’s top piano contestant at one time or another. Should we ban one or the other to avoid any possibility of favoritism?… Fortunately, each teacher has only one vote on the jury.”

For an issue based primarily on personal tastes, the debacle led to remarkably widespread and generally positive effects. The competition adopted new jury procedures including computerized score analysis and cumulative scoring. The organizers wanted to create a system that would promote comfort for everyone involved.

Yet, hurt feelings ran deep. A rift was opened between the Casadesus family (who felt attacked by the accusations of corruption) and the Clevelanders (who had grown intimately attached to the competition and cared deeply for its reputation). This rift would widen over the coming year and a half, culminating in a massive restructuring of the competition’s organizing body.

In the end, things worked out for the competition. Rosenberg’s comments inspired reactions that even he did not predict, including some that he specifically stepped back from, but they also sparked a change that had been in the working for years. After subsequent competitions, organizers have occasionally heard from audience members who disagreed with the outcome, but never to the extent that they had in 1993. This was a year when the audience members themselves seem to have taken on the roles of winners and losers, reacting to the pianists’ fates as if they were their own. It certainly shows how invested the Clevelanders were in our city’s world-renowned competition—something to read more about next time.

Suzanna Feldkamp is a Ph.D. student in the musicology area at Case Western Reserve University. She has an M.A. and B.M. from Michigan State and conducts research on thirteenth-century French popular song.