By Suzanna Feldkamp

When William Eves showed up to his piano lesson at Fontainebleau a little worse for the wear, his teacher simply smiled and said, in his thick French accent, “Too much ‘olland.” He had hopped on a train to the Netherlands for a weekend visit, taking full advantage of the 40.5% discounted train tickets that students received in France in 1936. It was the height of the Depression, and Eves had only managed to raise the money to get from Maine to the famous French American conservatory outside Paris by selling hand-knit goods, freshly grown vegetables, fudge, and shellacked paintings within scallop shells for months. This was only a summer session; Eves couldn’t be sure he’d be back. He didn’t want to squander an opportunity to see “‘olland” or the rest of Europe, for that matter. His teacher didn’t want him to either.

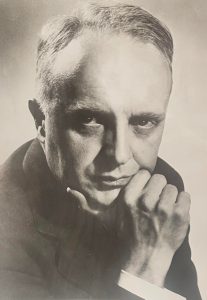

Robert Casadesus was a rigorous teacher, but he wasn’t harsh. Kind, sincere, and compassionate, he encouraged his students to take time to build a meaningful life away from the piano, while also keeping his musical standards high. Robert believed in efficiency, teaching his students to concentrate with utmost intensity in short practice sessions—three hours maximum. They did not always succeed. Another student, Larry Walz, recalls a lesson which was “not exactly good,” and being informed over lunch that he was to meet with Gaby Casadesus for an extra session. She got straight to the point: her husband was very displeased, and she was there to whip Walz into shape. “She looked out of the windows at the darkening sky and remarked, ‘I think there is going to be a storm.’ To this day, I don’t know if she was referring to the elements or my lesson.”

Together, Gaby and Robert make the deepest roots of the Cleveland International Piano Competition, founded in 1975 as the Robert Casadesus International Piano Competition. Gaby worked to establish the event in her husband’s memory shortly after Robert died in 1972, at 73 years old. Their relationship sprang from and continued to center around music as they grew older: even Gaby’s memoire is titled Mes Noces Musicale, or “My Musical Marriage.” They met at the Paris Conservatory during WWI, shortly after which Robert was deployed. He began to court her “by correspondence” just before the armistice was signed, and continued while he finished his service at Versailles and then Paris. They were married in 1921.

Together, Gaby and Robert make the deepest roots of the Cleveland International Piano Competition, founded in 1975 as the Robert Casadesus International Piano Competition. Gaby worked to establish the event in her husband’s memory shortly after Robert died in 1972, at 73 years old. Their relationship sprang from and continued to center around music as they grew older: even Gaby’s memoire is titled Mes Noces Musicale, or “My Musical Marriage.” They met at the Paris Conservatory during WWI, shortly after which Robert was deployed. He began to court her “by correspondence” just before the armistice was signed, and continued while he finished his service at Versailles and then Paris. They were married in 1921.

Gaby and Robert were both first-class pianists, but Robert’s break came when he was asked to step in for a sick pianist in a performance of Beethoven’s fourth concerto at the Paris Opera. He went on to perform over 3,000 concerts throughout his career. The quantity is impressive, but the quality he upheld through all of it is admirable. A letter he received from the infamous music theorist Nadia Boulanger, who worked with him at Fontainebleau, is a testament to the regard and acclamation he garnered from his colleagues. Boulanger wrote, in March 1945,

“Such perfection, such dignity, such taste! I must thank you. It is so seldom that one feels a joy of this quality—it goes a thousand times beyond its true reality… Your mastery, your thinking is of too much importance to let it pass by without stressing it. And from the bottom of my heart and the depths of my thoughts—as an artist—I come to congratulate you with a real joy and great pride… Everything depends on the upholding of values in the name of which you develop your art and, if I may, your soul.” (33)

Robert was ostensibly destined to be a musician. Born in Paris in 1899, the Casadesus family was well known for their many successful creatives, many of whom deeply influenced Robert as he grew up. In her memoire, Gaby recalls the day Robert lost his grandfather. That morning, he learned that he had received a prize at the conservatory.

Robert was ostensibly destined to be a musician. Born in Paris in 1899, the Casadesus family was well known for their many successful creatives, many of whom deeply influenced Robert as he grew up. In her memoire, Gaby recalls the day Robert lost his grandfather. That morning, he learned that he had received a prize at the conservatory.

“He went to tell [his grandfather] the good news before going upstairs to the studio to show his uncles his exam. When he came back down, he found him dead, his newspaper on his lap. His grandfather was a little tired since he had had bronchitis a short time before, but nothing suggested such a sudden death. Did he die of joy at the news of his grandson’s prize? Robert was deeply affected by his sudden death. His grandfather meant a lot to him, and his entire life he remembered hearing him play the guitar or mandolin at night before going to bed” (15).

The same seems to have been true for Robert’s family, friends, colleagues, and students after he died: they cherished and celebrated memories of his music. Of their travels to the U.S., where Toscanini heard his New York debut and invited him to play with the New York Phil. Living next to Albert Einstein in Princeton and performing recitals with the famous scientist. Intimate collaborations with Ravel, with Leonard Bernstein, with George Szell. Composing dozens of works and recording one of the largest discographies of the 20th century. Creating an international piano competition was just one way they celebrated those memories. Through hard work and dedication, it would become one of the most renowned classical music competitions in the world.

The prize Robert won the morning of his grandfather’s death would forever be tied to memories of that formative relationship. And even though the CIPC no longer carries Robert’s name (the reason why is a story for another day), we celebrate his legacy and know that it will be forever tied to the prizes that promising pianists receive in our competition. Robert was admired by his colleagues, family, friends, and students alike. This was a teacher who drew students like a magnet—who inspired such things as selling shellacked seashells if it afforded the opportunity to study with him. It’s not something to forget.

As we at Piano Cleveland work to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the Cleveland competition, we reflect on what brought us to this point. Travelling into the archive, it would be impossible to miss Robert’s mark. When I ask myself how to inspire appreciation for this history, I like to think of the advice Robert gave William Eves when he came to his piano lesson off a train from far away: “Begin as though the music has always been playing.”

Sources: institutional documents; Gaby Casadesus, Mes Noces Musicales (Paris: Buchet Chastel, 1994); articles within the special issue on Robert Casadesus, Piano Quarterly 30, no. 119 (Fall 1982).

Suzanna Feldkamp is a Ph.D. student in the musicology area at Case Western Reserve University. She has an M.A. and B.M. from Michigan State and conducts research on thirteenth-century French popular song.